When you’re right, Austenacious readers, you are right.

We talked a bit about Elizabeth Gaskell earlier in the summer (check the comments!), and here I am, about a third of the way through North and South. And, you guys, it’s awesome.

I know: this site is not called Gaskellacious. But! The Jane is strong in this one: it’s like a bridge, chronologically and thematically, between Austen and the Victorians. Published by Charles Dickens in his periodical Household Words, I like to think of North and South as a handy metaphor for (early-to-mid-) 19th-century British literature as a whole: drawing room romance, drawing room romance, drawing room romance, and then—BAM!—Industrial Revolution.

(At least, I think this is how it goes. A word about the edition I’m reading: it is one of exactly two copies in the possession of my local public library system, and I am pretty sure somebody—DigiReads, apparently—printed it off the internet and hand-glued it into a vaguely Victorian-print paperback cover, in much the way my junior-high self used to print out X-Files fanfiction and store it in three-ring binders for optimum access at key future moments. It’s riddled with errors, mostly missing punctuation. GoodReads tells me it’s a professional edition, but Penguin Classics, where are you and your air of publishing legitimacy when I need you? [Answer: Checked out.])

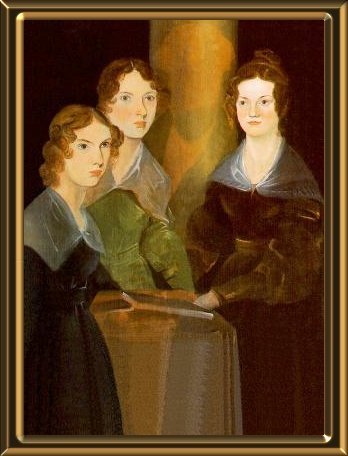

Anyway, North and South starts like Austen—in the titular South, with a stroll in a country garden and a surprise proposal. Its heroine is decidedly Austenian: eighteen and a clergyman’s daughter, a lover of nature, unprepared for romantic love and sometimes socially misunderstood. Its primary love story is built around a clearly Pride and Prejudice-esque relationship, in a “Boy, she’s haughty”/”Boy, he’s mean to the poor”/”Wellll, maybe we had it all wrong I love you I love you” kind of way. (I assume I know where this is going. OR DO I?) Then comes the North, and things change. Suddenly the subject matter is far more Dickensian—smoky air, factory girls, death by industrial accident—but only the subject matter. The voice remains all post-Austen, all the time: it’s the third-person narrative of a young lady and her parents, a couple of not-very-interesting suitors, one very interesting eventual-suitor, some impoverished neighbors, and her lucky girl cousin who got married and moved to Corfu instead of the gross but unexpectedly nuanced industrial town. And this is why I like North and South: it isn’t the urban melodrama of Dickens (though I like a wackily-named poorhouse as much as the next girl) and it isn’t the moody saga of the moors, like Gaskell’s pal and biography subject, Charlotte Bronte (though not much beats a crazy wife in the attic). It’s early Victoriana—the voice of the Regency confronted with a whole new modern world, and still working through the repercussions. Do we know what Jane would have done in the face of factory labor and slavish working conditions? We do not. But Gaskell might give us a hint.

Further reports as the story progresses; watch this space.

Better yet, go find yourself a nice social novel/romance and call me in the morning.